Unprecedented times call for unprecedented measures. This age-old adage certainly struck true as the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) issued an emergency declaration in March to suspend long-haul trucking hours of service (HOS) regulations1 that have been in place since the 1930s. The goal of this unprecedented declaration: to allow cargo distribution networks to operate as efficiently as possible during these times of rapidly changing directives from federal and local governments. In a country where 71.4% of all freight tonnage is transported over the road,2 truck routes are our country’s backbone, but they are often taken for granted in the age of two-day delivery. The coronavirus pandemic has led to empty paper goods aisles and far worse, dwindling hospital supply closets. In times like these, we rely on the tireless resilience of truckers nationwide, and they are currently stepping up to meet the need.

It goes without saying that in this situation, the safety and well-being of our fellow human beings are paramount and all efforts should be focused on preserving human life. However, there is a trickle-down effect of this pandemic that permeates almost all aspects of life. One area that is likely to see more than a trickle is on the highway, where commercial trucking regulations have been eased while other drivers have been mandated to stay off the road. The net effect of that seesaw is crucial to the safety of truckers in the coming months and subsequently will be of interest to commercial auto insurers.

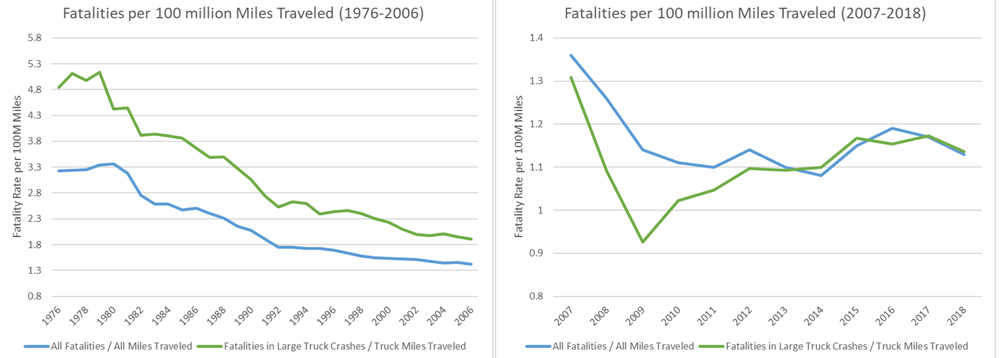

The struggles of the commercial auto market have been discussed extensively given that the business segment hasn’t returned an underwriting profit since 2010.3 The phenomena of social inflation and enormous adverse verdicts have led to increased losses and reactive rate increases. Often, the large claim payments contributing to the profitability struggles involve large trucks and/or fatalities. As shown in Figure 1, large truck vehicle fatalities as well as overall vehicle fatalities saw a steady decline from 1976 until roughly 2009. Since then, the overall fatality rate has been relatively flat, trending at +0.5%, while deaths in large truck accidents have been increasing at an annual rate of 2.2%.4

Figure 1: Historical crash-related fatality rate per 100 million miles traveled

Distracted driving is often blamed for the recent flattening of the overall vehicle fatality curve, but there are other causations at play, especially in regard to trucking. Given that the fatality trend appears to change around 2009, in the heart of the 2007-2010 global financial crisis, another possible theory is that the health of the economy has an influence on driving behavior. A recent Milliman article observed an inverse relationship between private passenger collision frequency and the unemployment rate.5 It seems plausible to believe that a similar relationship exists for trucks as well given their key role in an expanding economy. Monitoring this relationship will be especially important as we see unprecedented increases in unemployment coupled with decreased traffic from stay-at-home measures.

Intuitively, less congested roadways would seem likely to lead to a lower frequency of commercial auto claims. However, determining the exact factors that cause commercial vehicle accidents can be challenging today given the lack of uniform reporting and the inability to decisively attribute an accident to a cause that may be unmeasurable. For example, it is easy to determine whether a driver was under the influence of alcohol at the time of a crash, but difficult to identify whether an accident was caused by driver fatigue. Commercial telematics is beginning to address the lack of data, but will need to be used on a broader scale before we can draw definitive conclusions.

Despite these hurdles, there is nationally representative data that looks at factors contributing to truck accidents. Several of these factors are summarized in Figure 2. In terms of factors directly related to congestion, historical data suggests that “Traffic Flow Interruption” was a leading contributor to accidents, coming into play for 28% of truck crashes. Other accident factors likely to experience a reduction under COVID-19 traffic scenarios include “Inadequate Evasive Actions” (a factor in 6.6% of truck crashes), “Following Too Closely” (4.9%), and “False Assumption of Other Road Users Actions” (4.7%). It is worth noting that one in four truck crashes do not involve another vehicle, and the frequency of these single-truck accidents may be relatively unaffected by lower congestion.6

On the flip side, suspending hours of service requirements is likely to increase the frequency of commercial auto claims, with driver fatigue being the primary factor. The emergency declaration does not forgo all HOS regulations, but it does eliminate the weekly 60/70 rule and allows continued operation without 30-minute breaks. A 10-hour off-duty provision is still in place after completing a route. Data collected while the HOS regulations were in place suggest that fatigue is a factor in 13.0% of truck crashes. Other fatigue-related factors such as “Inattention” and “Driver Pressured to Operate Even though Fatigued” came into play 8.5% and 3.2% of the time, respectively.8 While we are likely to observe increases in accidents due to these factors, it is difficult to say what the offsetting effect will be due to fewer personal vehicles on the road.

Figure 2: Factors contributing to truck crashes (percentage of accidents where the factor was present)

Another item that complicates the trucking environment is the closure of rest stops and restaurants to encourage social distancing. Drivers are also encountering situations where they are unable to access facilities at their delivery sites due to new company policies on contactless delivery. Although truckers may not be required to take 30-minute breaks, they will still need to make stops to use the restroom and eat. The lack of options to accommodate these breaks could further contribute to fatigue and even lead to rerouting. Although rerouting seems easy to overcome with the GPS technology available today, it may be concerning to truckers when considering that “Unfamiliarity with Roadway” is a factor in 21.6% of truck accidents.9

Accident frequency is not the only commercial auto consideration at play. Identifying a reliable exposure base for statistical metrics is largely in flux as well. The HOS relief is only given to drivers providing direct assistance in support of emergency relief efforts related to the COVID-19 outbreak. This includes the transportation of medical equipment, sanitation supplies, food for emergency restocking of stores, and anything else used to address the pandemic. 10 Based on the U.S. Commodity Flow Survey (CFS), we estimate that roughly 29% of ton-miles shipped contain commodities that could qualify for the HOS reduction, including items like pharmaceuticals, meats, and paper products.11 The short-term demand for many of these items has increased, but some will see a future reduction in demand as individuals slowly use their personal stockpiles. Additionally, not every item in these commodity classes would qualify, so the actual percentage affected could be much lower. While ton-miles are not a traditional actuarial exposure base (like vehicle counts or miles driven), it can serve as a reasonable approximation to get a high-level sense of the impact prior to more data coming in.

A counterbalance to the increased exposure discussed above is the many truckers not supporting relief efforts who have seen an abrupt drop in demand due to the pandemic. Commodities such as fuel, building materials, and manufacturing equipment are seeing noticeable declines. These commodity classes account for an offsetting 45% of ton-miles shipped.12 While this number seems significant compared to the 29% above, it is important to emphasize that these commodity segments are generally experiencing a slowdown rather than a complete halt in production. To further complicate the true impact, FMCSA has also announced that it would not be enforcing the temporary operating authority registration fee in an effort to encourage these truckers with decreased demand to begin carrying supplies to support COVID-19 relief efforts.13

Despite the numerous considerations above, we are still not considering all of the scenarios. What if large numbers of truckers become ill? How long will stay-at-home measures be in place? The HOS relief was set to expire on April 12 and was extended to May 15,14 but even disease control experts can’t determine what duration of social distancing will be sufficient. At the end of the day, there is certainly a lot of uncertainty. No one truly knows what the indirect impact will be on commerce and insurance. The best we can do until more information becomes available is continue to monitor the situation, and more importantly, protect the health and safety of our fellow human beings.

2American Trucking Associations (July 2019). Truck Driver Shortage Analysis 2019. Retrieved on April 14, 2020, fromhttps://www.trucking.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/ATAs Driver Shortage Report 2019 with cover.pdf.

3 National Association of Insurance Commissioners (2018). Report on Profitability by Line by State in 2017. Retrieved on April 14, 2020, from https://www.naic.org/prod_serv/PBL-PB-18.pdf.

4Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (December 2019). Fatality Facts 2018: Yearly Snapshot. Retrieved on April 14, 2020, from https://www.iihs.org/topics/fatality-statistics/detail/yearly-snapshot.

5Anderson, P., Krafcheck, E.P., & Pipkorn, K.A. (March 27, 2020). Nowhere to Drive: The Impact of COVID-19 on the Auto Insurance Industry. Retrieved on April 14, 20920, from https://www.milliman.com/en/insight/nowhere-to-drive-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-the-auto-insurance-industry.

6U.S. Department of Transportation (November 2005). Report to Congress on the Large Truck Crash Causation Study. Retrieved on April 14, 2020, from https://ai.fmcsa.dot.gov/downloadFile.axd?file=LTCCS%20reportcongress_11_05.pdf.

7FMCSA (March 13, 2020). Emergency Declaration Under 49 CFR § 390.23 No. 2020-002. Retrieved on April 14, 2020, from https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/emergency/emergency-declaration-under-49-cfr-ss-39023-no-2020-002.

8U.S. Department of Transportation (November 2005), op cit.

10FMCSA (March 13, 2020), op cit.

11Bureau of Transportation Statistics (December 19, 2018). 2017 CFS Preliminary Data. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from https://www.bts.gov/surveys/commodity-flow-survey/2017-cfs-preliminary-data.

13FMCSA (March 20, 2020). Notice of Enforcement Discretion – Emergency Declaration 2020-002 – COVID-19 – 03-20-2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/emergency/notice-enforcement-discretion-emergency-declaration-2020-002-covid-19-03-20-2020.

14FMCSA (April 8, 2020). Extension and Expansion of Emergency Declaration No. 2020-002 Under 49 CFR § 390.25. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/sites/fmcsa.dot.gov/files/2020-04/ExtensionofEmergencyDeclaration2020-002a.pdf.